A raw, rainy Sunday in April. Eli, my horse, running laps in the indoor arena, suddenly takes a bad step. Our eyes lock for an instant; I see pain, fear, confusion. He sees my horror.

He can’t stop right away; there’s no jockey to pull him up, and he’s moving too fast for me to grab. He’d been at this too long, a big chestnut blur galloping around and around at breathtaking speed. I should have stopped him. Why didn’t I? I was chatting, not paying attention.

This is my fault.

I forget to breathe as I watch him hobble another half lap around, doing God knows how much more damage before hitting the brakes, finally. We race over, my trainer and I. Christee feels his right leg while I hold his head and try to soothe him. A thin sheen of sweat coats his neck, slick and hot under my hand. He is trembling. It takes us fifteen minutes to get him out of there, one brutal step at a time, inching our way to the hose, baby steps, so we can run cold water over his leg before it swells.

I think of Barbaro. I think of Eight Belles. It’s impossible not to think of them, along with all the other, less celebrated Thoroughbreds like mine, horses that shattered their bones as they ran, doomed by their own engineering.

The water doesn’t help. We add insult to injury, squirting two grams of bitter bute paste, a painkiller, down his throat. I fluff up his stall with an extra bag of pine shavings and throw in an armload of hay, things you do when your horse is hurt and you are helpless. I go stand by his head and feed him carrots – the first tastes like bute, so he spits it back out – then I talk to him softly, pianissimo, while he chews.

I tell him I’m sorry. I don’t know yet what’s wrong, but I can see he’s in pain. I ask him to stand quietly. I promise I’ll be back first thing in the morning, and we’ll figure this out and we’ll fix it. Hang in there, I tell him. I love you.

We are eyeball to eyeball, my racehorse and I, mine blue, his a rich caramel brown with gold flecks and a fringe of stiff reddish lashes that tickle my face as he blinks. I kiss the little dent over one worried eye, the furry spot beneath his ear, the white star on his chestnut forehead.

Then I get in the car for the hour drive home, to walk the dog, make my husband’s dinner, and go to bed, where I will lie awake flogging myself until dawn, when it will be time, mercifully, to return.

***

Unlike dogs, whose facial muscles allow for a considerable range of expression, horses rely more on ear and tail position, vocalizations and overall body language to communicate. But that isn’t to say they lack emotional range.

In his more affectionate moments, Eli likes to rest his chin on the top of my head, or burrow under my hair and snuggle my neck. He’s learned to give kisses – a surefire guarantee of a treat – by gently brushing my cheek with his rubbery lips. Now and then, he will give me a backrub or a neck massage using his nose and his lips. He’s perfected the art of poking his velvet muzzle over the top of his stall door or between the fence rails of his paddock at the sound of a carrot snapping in two. Pavlov’s horse.

When faced with the prospect of an unpleasant chore – having his ears cleaned, his mane shortened or his medicine dispensed, he elongates his neck giraffe-style. He hates having his face washed, and will launch evasive maneuvers at the sight of me brandishing a wet wash cloth. On those rare occasions when I turn my attention to others, he has no trouble expressing his jealousy. Once, when I hugged a friend in his presence, he inserted his entire head between us.

At 16.2 hands, he is tall for a Thoroughbred, five-foot-four at the shoulder to my five-foot-two. He outweighs me nearly ten times over, and with muscle accounting for more than 60 percent of him, he’s preordained to win every wrestling match. One well-placed kick from a back hoof can exert a force roughly equal to a ton; fortunately, he hasn’t a mean bone in his body.

He does have a temper, however. An angry Thoroughbred is a sight to behold with his pinned ears and thrusting head, stamping his foot on the barn’s cement floor, throwing a shower of sparks.

More often, he’s playful, snatching the hose from my hand as I’m cooling him down, or nipping my sleeve then looking away, feigning innocence. He’s developed a begging routine subject to last-minute derailment should I fail to be charmed: his pawing right front leg morphing into an elaborate stretch accompanied by big phony yawn.

Turned loose when he’s feeling good, he squeals like a pig, a high-pitched “whee!” that’s two parts excitement, one part “watch out” – good advice, since it’s usually followed by a series of bucks. He loves to roll on his back then pop back up and rear before taking off running full-tilt. If I decline to play along, he tries to egg me on by running up to within inches of me and shaking his head in my face.

It’s when I’m sad or upset, though, that he truly displays the inherent sensitivity of his breed, planting himself in my path, bumping me with his nose, and standing eyeball to eyeball, peering into my soul.

I marvel at his complexity, his vast repertoire of moods. I’ve observed him being playful, affectionate, demanding, obstreperous, mischievous, pensive, needy, excited, rambunctious, petulant, lazy, frightened, fresh and forlorn, all within a single day, albeit a long and exhausting one.

More than anything, I love seeing Eli show off, tail held high, nostrils flared, trotting with his legs so extended he seems to be floating on air between strides. In all the years I’ve been watching him do this it never fails to quicken my heart.

***

God help me, she’s too young. The vet is too young, and she hasn’t even brought the right stuff. There’s no X-ray machine, no ultrasound. She feels Eli’s right front leg, zeroing in on the shoulder, then watches him take a few agonizing steps. She winces. “Put him back in his stall.”

Her name is Kim, and she’s fresh out of vet school. I follow her out to her truck, where she loads me up with painkillers and hands me a schedule for their use. I’m to check in with her the following day. We make tentative plans for her to come back with the X-ray machine the day after that. In the meantime, Eli is not allowed out of his stall.

“Not even to clean it?”

“Clean around him,” she says, and is gone.

It costs $95 just for her to walk in the door, apart from anything else she might do, and I’ve just spent it learning absolutely nothing.

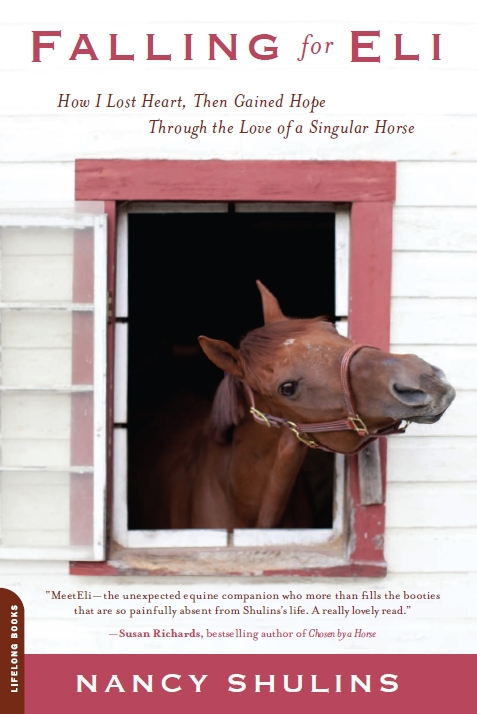

Back in the barn, I find Eli in the same position as when I left him, leaning against the back wall. His stall is airy and bright, slightly bigger than the rest, and I pay a little extra for it. Mornings, he likes to hang his head out the window and watch for my car, greeting me with a throaty nicker. Hi, Mom.

I grab a handful of carrots and am about to go in when I see his head droop. He’s taking a nap. I whisper sleep tight and go home.

The next day, I call Kim from the barn to report he’s no better, and to ask a favor. “It’s nothing personal, but if I’m going to be facing a horrible decision, I’m going to need someone with a bit more experience to advise me.”

What I’m hoping she’ll say is that I’m being silly; that whatever he’s done, it will not do him in.

Instead, she says: “I understand totally. I would never presume to tell you what to do. I’ll bring someone with me.”

I think: If I cover the mouthpiece, maybe she won’t hear me cry.

***

I keep calling Christee, my trainer, at her day job, pestering her with questions I know she can’t answer: Why didn’t we stop him? What do you think it is? Do you think it’s broken or just bruised? Are there bones a horse can break and still recover?

“I don’t know.”

“I know you don’t know, but what do you think?”

“I don’t think it’s broken,” she says finally.

“Why not? Based on what?” (This is me hammering her for trying to be reassuring.)

“Gut feeling. I just don’t think it is.”

Neither does the senior vet who accompanies Kim the next day to take endless X-rays of Eli’s right shoulder, pulling his leg straight out in front of him, then bending the knee, manipulating it in ways I imagine are causing him unspeakable pain that he’s too doped up to protest.

Under the influence of the fast-acting sedative, his fine Thoroughbred head feels like an anvil in my arms. His droopy lips leak saliva all over the protective lead apron that covers my chest. “It’s okay,” I whisper into his lifeless right ear, slack as a donkey’s. “They’re almost done. It’s okay.”

The two vets huddle over their X-ray machine, trying to gauge whether they have their shot. Shoulders are hard to X-ray, they tell me. So much muscle mass. A few more, just to be on the safe side.

I shift my weight, propping Eli’s head a little higher, feeling the ache in my back, welcoming it. So far, they’re not seeing a fracture, but that doesn’t mean it’s not there. The surgeon will review the X-rays later. He’s better at spotting these things.

I know what they’re looking for: A stress fracture, thin as a crack in a glass, somewhere along his right shoulder blade; a common racehorse injury caused by repetitive force, typically galloping. If caught in time, a stress fracture can heal, but it takes months and requires immobilization lest it propagate into the joint.

If Eli has a stress fracture that extends into a joint, I am going to lose him.

Kim grabs his tail to help steady him as I lead my poor drunken gelding back into his stall, taking out every last bit of hay he could choke on. He’ll get it back when he’s fully alert. I watch him sleep, wondering how many times I’ve done this very thing, waiting for a sedative to wear off, for him to open his eyes. Wanting to be the first person he sees when he’s sick or scared, stressed or defenseless.

“He’s such a nice horse,” Kim says, watching me watch him, “And such a good patient.”

“He’s had plenty of practice,” I reply, “unfortunately.”

“How far do you want to take this?” she asks. “You need to be thinking about that.”

I listen without comprehension, as if she’s speaking a language I don’t understand.

But I do, of course. That night, I have the nightmare: I’m leading Eli to a giant hole in the ground. He goes trustingly, willingly, with no sense of betrayal, snatching the occasional mouthful of grass as we go, each step bringing him closer to the prick of the needle, the very last thing he will feel on this earth. I wake up in a panic.

Leading a horse to its own freshly dug grave is actually a best-case scenario. A horse that dies in a stall ends up being dragged behind a tractor; one sold for slaughter goes to a rendering plant, to be processed along with rancid meat and unwanted dogs and cats into soap and cosmetics, crayons, candy and lard.

I’ve mostly kept a respectable distance between my conscious mind and the notion of Eli’s demise, reminding myself that he’s only six, ten, fifteen, eighteen years old. Like people, horses are living longer, for many of the same reasons: advancements in medicine, nutrition and care. Horses can live well into their thirties. Eli and I should have many more good years together.

But with the possibility of a broken shoulder, the brutal logistics of equine mortality are suddenly staring me in the face. The hole in the ground is nothing compared with the one he’s going to leave in my life, a hole so huge it took twelve-hundred-fifty-three pounds to fill.

***